Economic relations between the Gulf monarchies and Asian countries are running fast. In these partnerships, however, the defence dimension of economy is advancing slower than other components. The shining pavilions of Gulf capitals’ defence exhibitions now host many Asian firms, especially from China. Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates (UAE) are signing several defence industry deals with Asian states to boost national capabilities on arms and ammunitions production. Cooperation on defence technologies and AI is also already a reality. Moreover, joint military drills between Arab Gulf and Asian states, especially in the naval domain, are increasing in numbers and frequency, and often include Beijing.

However, the Gulf monarchies continue to purchase a very low number of weapons from China, with American and Western providers still outnumbering Asian companies in defence procurement. This is a decision based both on politics and strategy . On the one hand, Saudi Arabia and the UAE aim to build indigenous national defence industries, and upgrade air defence in light of increasing Iranian-related threats; on the other, they don’t want to fill their arsenals with weapons that can’t be integrated with US and NATO systems. Given this context, the focus of UAE and Saudi Arabia’s weapons acquisitions from China is air defence (drones, missiles). The goal is defending national boundaries from Iran, its non-state armed allies and proxies in the region, while putting pressure on the US toward tightened security guarantees from Washington.

A ´Vision-First` Strategy: Rising Defence Industry Agreements

Since mid-2010s, the UAE and to a lesser extent Saudi Arabia signed, in the framework of post-hydrocarbons diversification processes, many defence industry agreements with Asian companies from China, India, Indonesia and Malaysia. Industrial deals regarding UAVs technologies, but also naval and land domains. The aim is to shape national capacities in weapons production and maintenance while boosting the non-oil sector. In 2017, the Saudi kingdom allegedly signed a deal with China to establish drones manufacturing facilities in Saudi Arabia. In 2015, the Emirati Abu Dhabi Ship Building and India’s Reliance Defence started a partnership aimed at the construction of naval ships, including frigates and destroyers. In 2020, the UAE’s International Golden Group and China North Industries Group Corporation Limited (NORINCO) launched the China-Emirates Science and Technology innovation laboratory (CEST), a joint project focused on research and development in the field of drones.

In 2023, the Emirati CARACAL company, a small arms manufacturer part of the national conglomerate EDGE, signed an agreement with the Malaysian Ketech Asia firm to locally produce and resale tactical assault rifles in support of the Royal Malaysia Armed Forces requirements. In 2023, EDGE also signed a memorandum with India’s Hindustan Aeronautics (HAL) to cooperate on joint design and developing of missile systems and drones. In 2024, EDGE and the Indonesian state-owned defence manufacturer PT Pindad agreed on a 27 million dollars deal to supply an ammunition production line: the production will begin in 2026 and will be located in an Indonesian facility.

China Shines at Gulf Defence Fairs, But Arms Export to the GCC Is Still Low

Since the mid-2010s, Gulf monarchies have begun purchasing Chinese armed drones and missiles. Air defence continues to be the focus (with Chinese UAVs deployed also in the Yemeni and Libyan conflict theatres), while no significant acquisition of land and naval assets appear. In recent years, the presence of China’s firms at defence exhibitions in the Gulf has definitely risen in numbers and visibility. Chinese pavilions are often larger than American ones. Nevertheless, this hasn’t been translating into a surge in Chinese weapons acquisitions by Saudi Arabia and the UAE.

At the 2023 edition of IDEX, the International Defence Exhibition in Abu Dhabi, Beijing was present with dozens of firms. At the 2024 Unmanned Systems conference in Abu Dhabi (UMEX), China was the second largest state, after the UAE and ahead of the US, in terms of the exhibition space accounted for its companies: more than 50 firms were listed. At the Saudi World Defence Show 2024, China’s floor space reached 4.668 square meters, the largest of the fair and bigger than the US (3.335 square meters). Still, Beijing –which displayed the Wing Loong armed drones and, for the first time, performed an aerial demonstration- listed 36 companies against the more than 100 Washington firms present.

Numbers shed light on a reality that is very different from perceptions. According to the SIPRI, Saudi Arabia imported 245 million dollars’ worth of arms from China between 2010-2020, against the over 19 billion dollars from the US. Since 2017, Riyadh buys Chinese Wing Loong armed drones. Media reported that in 2022 (so following previous SIPRI estimates) Saudi Arabia signed 4 billion dollars arms deals with China, comprising armed drones and ballistic missiles.

Between 2010-2021, the UAE imported from China 166 million dollars worth of weapons, and 7.3 billion dollars from the US; in the same period, Qatar acquired arms for 118 million dollars from China, while 2.3 billion from France and 4.2 billion from the US. Oman and Kuwait instead wouldn’t import weapons from China at all.

About defence procurement from the East, the UAE has focused on air defence as well. Since the mid-2010s, the Emirati federation has acquired multiple-rocket launchers from China (as Bahrain did) and South Korea. During President Mohammed bin Zayed Al Nahyan’s state visit in Seoul in late May, the UAE and South Korea announced the expected removal of all tariffs on South Korean’s arms exports, as for the Comprehensive Economic Partnership Agreement (CEPA) agreed in 2023. Abu Dhabi bought for the first time Chinese Wing Loong drones in 2015, before Riyadh, and in 2022 ordered fighter jets from China and signed contracts for an undisclosed number of medium-range missiles from South Korea. Qatar has included Chinese short-range ballistic missiles in its arsenal. With regard to naval defence, the UAE signed in 2023 a contract with PT Pal Indonesia to acquire multi-role support ships to improve expeditionary capabilities.

Defence Diversification vs Integration: The Gulf Interoperability Issue

For Saudi Arabia and the UAE, partnering with Asian states’ companies promotes national defence industry efforts. The goal is achieving greater localisation in the production of weapons and ammunitions to strengthen the non-oil sector and, at the same time, supporting “defence autonomisation” for hardware (arms) but also for the software i.e. the human skills component. Therefore, Gulf monarchies’ investments with Asian defence companies fit into the ultimate “Vision” goal of building national tools and capabilities, also in the defence field.

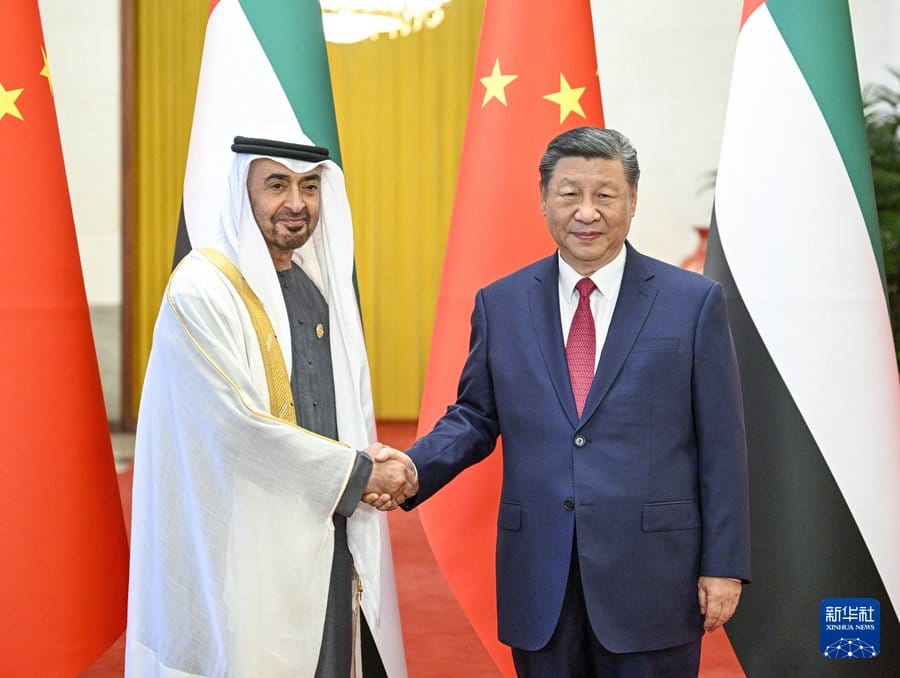

Defence procurement is instead a different story. The limited number of weapons Saudi Arabia and the UAE import from Asian states–although on the rise-, and with particular regard to China, reveals a political and strategic rationale. Surely, Abu Dhabi and Riyadh are buying Chinese drones and missilesto enlarge their “air defence toolkits”, especially as Iranian-related asymmetric threats in the region multiply. Still, they also do it to keep the pressure high on the US to obtain written security guarantees on mutual defence. The UAE even performed its first-ever (and first-ever also for a GCC state) air drill with China, “Falcon Shield”, in Xinjiang in August 2023, while their air force chiefs met in Beijing in April 2024 to discuss further cooperation. As Mohammed bin Zayed’s visited China in June 2024, Abu Dhabi and Beijing stressed to be ready to exchange experiences on defence and security.

However, Gulf monarchies’ enduring big import divide between US, Western weapons and Chinese arms suggests Arab Gulf states know that too much diversification in weapons providers would hamper the ongoing defence integration process with the US. Something that would weaken their overall defence standing vis-à-vis external threats.

In such a picture, the timing of defence integration between the US (more broadly NATO members) and the Gulf monarchies is decisive. The Commander of CENTCOM General Michael “Erik” Kurilla clearly stated in 2023 that the American challenge is pushing ahead integration with the GCC states –thus enabling interoperability- before China starts to export higher and more sophisticated weapons.. Indeed, “this is a race to integrate before China can penetrate”.

For the Gulf monarchies, the defence dimension of economic diversification really requires a careful balancing act between the US and China, especially since the American-Chinese technological competition has become systematic. However, this is a (multipolar) reality that Saudi Arabia, the UAE and the other monarchies have learned to navigate well. Being aware they can’t detach from Asia, and especially China, for post-oil economic projects. And from the US for defence.